I’ve read a few books lately that have taught me something that surprised me:

Most of those writing rules you’ve read about? They don’t matter.

Well, let me clarify. They do matter, and many of them are good advice. But they don’t matter as much as this one rule:

Don’t be boring.

Let me explain what I mean by looking at three works of fiction I read or viewed lately. I’ll start with a national bestseller book-club-type book: The Light Between Oceans by M. L. Stedman.

Now, this book was Stedman’s debut, but it still earned an international bidding war among publishers. It stayed on the NY Times bestseller list for years. Amazon has over 14,000 reviews for this book, averaging 4.5 out of 5 stars. People like this book, almost overwhelmingly.

But it breaks all sorts of rules. Stedman darts in and out of way too many people’s POVs, and sometimes it adds little to the story. If I were her editor, I might advise her to cut some or even several.

It starts in the “wrong” place. All the writing advice says to start when the story gets interesting, which is when Tom and Isabel find the baby. And yes, that happens in the very first chapter, but then we go back in time to right after the war, and when they are courting, and when Tom first becomes a lighthouse keeper. This goes on for a LONG time, and all the while, I wanted to find out what happened *after* they found the baby, because that’s the real story. If I were Stedman’s editor, my first instinct might be to advise her to trim or even eliminate the backstory chapters. (Now that I’ve read the whole book, I do think I would have weakened the book to cut it entirely. My first instinct was probably wrong.)

Worst of all, Stedman changes tense constantly. Constantly. And yeah, some people say she’s using that for effect (I have my doubts), but the fact is, shifting tense is generally seen as a no-no, and she does it.

Now, if The Light Between Oceans had been a badly written book, or even a mediocre book, people would have been latching onto these things as evidence of how it failed to impress them. But when the book is good? Nobody cares. People assume departures from the rules were intentional.

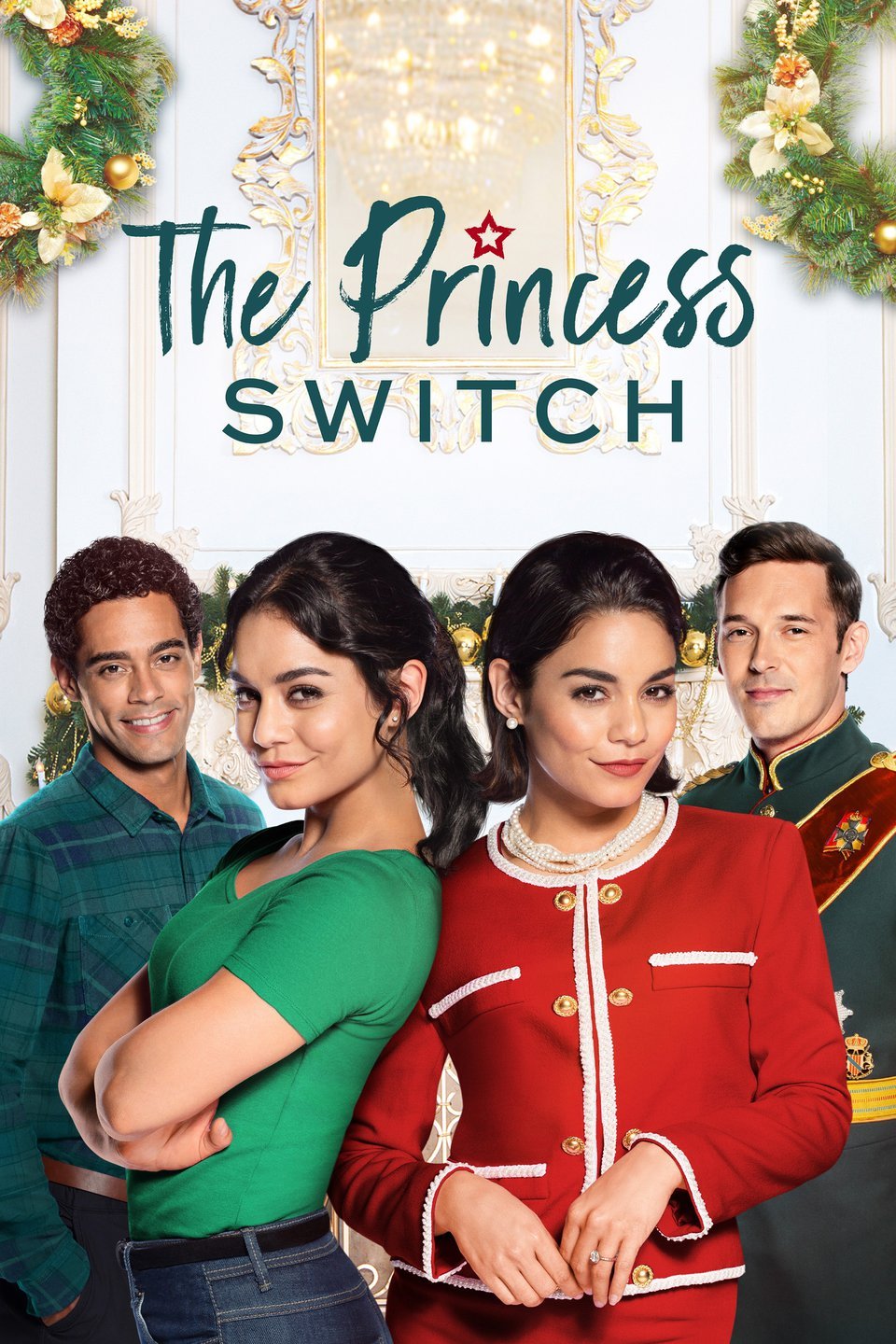

Next: The Princess Switch (Netflix original Christmas movie)

Folks, this movie isn’t especially intelligent. It really strains belief over and over and over (don’t get me started on the stand mixer). It isn’t even new: Mark Twain essentially wrote this story (minus the romance) in 1881.

Folks, this movie isn’t especially intelligent. It really strains belief over and over and over (don’t get me started on the stand mixer). It isn’t even new: Mark Twain essentially wrote this story (minus the romance) in 1881.

You know what it isn’t? Boring.

It gets right into the conflict and keeps making things as difficult for the main characters as possible. Every scene leaves you wondering how on Earth everything is going to end up okay.

As I was watching this movie, I kept thinking, “This is so cheesy. This dialogue is so bad. Yeah, right. The acting could definitely be better.”

And yet. I watched the whole thing, and even now that I’ve finished it, I felt like I ate the worst junk food imaginable and regret nothing. It was fun. It was compelling.

Okay, the third work I’m going to discuss is a counterpoint to the others. It’s a book that, on paper, looks nearly perfect. Beautiful prose, careful character development, deeper meaning, novel setting. And yet.

Folks, I could barely get through it. I kept thinking something more compelling would happen, and it never did. The book is Beautiful Blue World by Suzanne LeFleur. Now, I do admit that my opinions on this book are my own and that others may have reacted entirely differently to this book.

First off, isn’t that cover gorgeous?

First off, isn’t that cover gorgeous?

Okay, on to what didn’t work for me in Beautiful Blue World, and, ultimately, what it means to be compelling.

The book is about a girl whose best friend is top of her class at their school. They live in an alternate Europe fighting an alternate World War II. It’s announced that the war effort is in need of children who can pass a certain test. These children will leave their families to help in the war effort, but their families will receive a stipend in exchange. The MC’s friend plans to take the test, so MC does too. Medium spoiler: MC passes; friend doesn’t.

And then . . . not much happens. The theme is the importance of empathy, which is something I definitely agree with.

What is missing is a real conflict, which I will talk about in a moment, and high enough stakes. Conflict + stakes = compelling.

A conflict occurs when a protagonist wants something really, really badly but can’t have it, at least for the moment. It’s Tom and Isabel desperately wanting to keep their baby even though they know that doing so is hurting someone else. It’s Stacey and Margaret each falling in love with the other one’s man–impossible to maintain once they return to their own lives. It’s Frodo trying to get the One Ring into Mount Doom and the rebel fleet taking on the Death Star.

If you have an interesting conflict, readers are going to be willing to put up with a lot more imperfection from you than if you don’t. That isn’t to say that you don’t need to work on making your book the best it can be, but it does mean that if you don’t have an interesting conflict, you need to focus on that first. Nothing else you do matters as much.

Then you need to establish high and personal stakes*. Stakes are what happens if the main character fails. So if someone really, really wants something they can’t have, the basic stakes are . . . they don’t get it. Okay, not that interesting usually. But if something catastrophic happens if you fail–and success seems impossible–that’s where a compelling story sits. If the whole world, including Frodo’s beloved Shire, will fall to Sauron if he fails, then he’s going to try no matter what hardships he faces, and he’s going to make sure he succeeds. And meanwhile, readers are going to be turning pages, desperate to find out how everything turns out.

The stakes in The Light Between Worlds are, on one side, that the guilt could eat Tom alive and tear their marriage apart, and on the other, that they could go to prison (or even worse). In The Princess Switch, the stakes are that people could find out what they’ve done and that all relationships involved could be irreparably damaged.

Beautiful Blue World makes an attempt at stakes (the MC’s hometown could be bombed, and she could lose everyone she loves), but it’s never clear what she needs to do in order to prevent that. It’s never clear what she wants. It’s never clear what the reader needs to root for, or dread.

So–set up a conflict that sizzles, ratchet those stakes up as high as you can get them, and make the stakes personal to your main character. Everything else is gravy.

*Other authors have written great posts about stakes. Here are links to some of them:

http://terribleminds.com/ramble/2013/07/16/25-things-to-know-about-your-storys-stakes/

https://www.helpingwritersbecomeauthors.com/story-stakes/

1 comment